Sister of Alberta Williams, murdered in 1989, hopes for justice from inquiry

SMITHERS, B.C. — The older sister of Alberta Williams, whose body was found in 1989 east of Prince Rupert, B.C., hopes a national inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women will help find the killer.

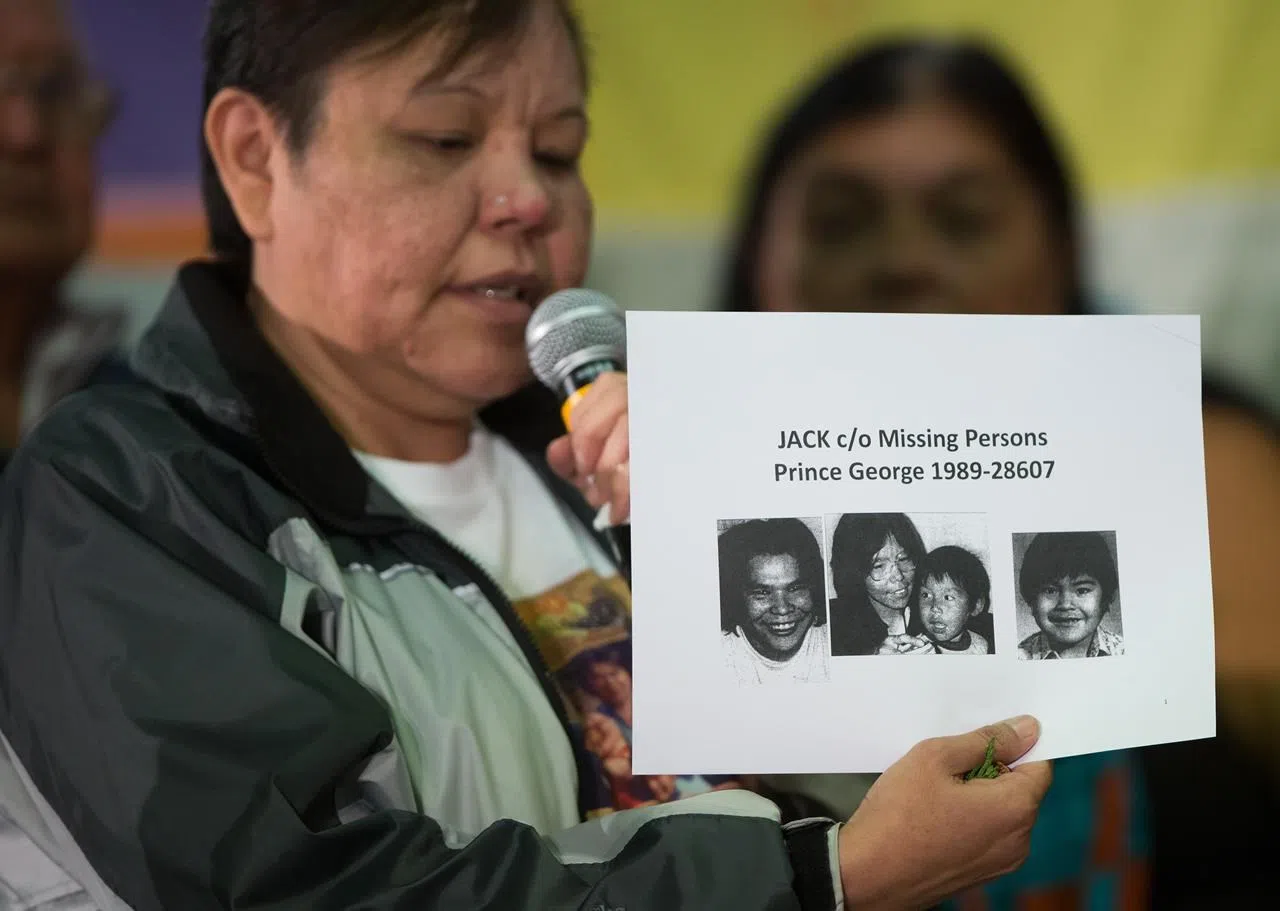

Claudia Williams and Garry Kerr, a retired RCMP officer who investigated the case, delivered powerful testimony together on Wednesday at the inquiry in Smithers, B.C.

The two haven’t seen each other in 28 years. Sitting on a bench outside the hearing, the pair described their emotional reunion on a flight from Vancouver a day earlier.

“I looked for him everywhere in the airport,” said Williams. “I was looking around, ‘Is that Garry? Is that Garry?’ … until I got on the plane. He was the one who recognized me.”