Montreal one step closer to getting park to mark Irish mass grave site

Montreal is one step closer to getting a commemorative park for the 6,000 Irish immigrants buried in unmarked graves in an industrial pocket of the city southeast of the downtown core.

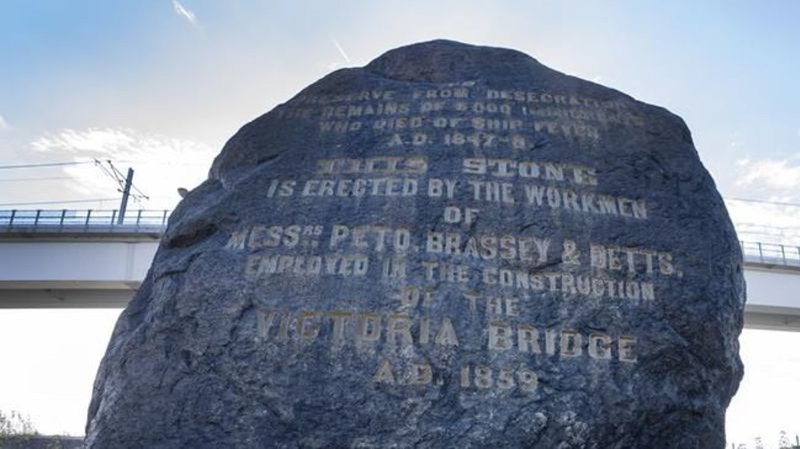

This week, the Montreal Irish Memorial Park Foundation became the new owner of the solitary monument known as the Black Rock, a three-metre-tall boulder that marks the location of the largest mass grave in Canada.

The site, previously the property of the Anglican Diocese of Montreal, consists of a small patch of greenery in the median of a busy street near the base of the Victoria Bridge, which links Montreal to the south shore of the St. Lawrence River.

The foundation says the land donation by the diocese was key to its goal to transform the area — passed by around 23,000 drivers every day — into a park honouring the thousands of Irish people who died of typhus in 1847 while fleeing Ireland’s Great Famine.