How the B.C. government approached land rights after major court ruling

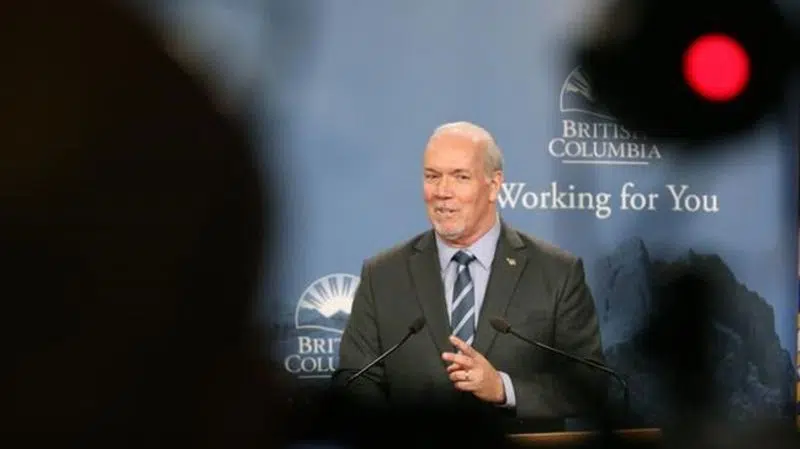

VANCOUVER — B.C. Premier John Horgan raised his voice over jeers and fist-banging recently in question period after members of the Opposition Liberals criticized his government’s handling of the clash between Wet’suwet’en hereditary clan chiefs and a pipeline company.

Horgan told the legislature that the unresolved rights being asserted by the chiefs were around long before his government took power 2 1/2 years ago.

“These issues have been percolating for generations — generations,” he said.

While 20 elected First Nations councils have signed agreements with Coastal GasLink over its natural gas pipeline, the clan chiefs say the pipeline has no authority to run 190 kilometres through their traditional territory without consent.