Sask. Gov’t firm on drug decriminalization, safe supply stance

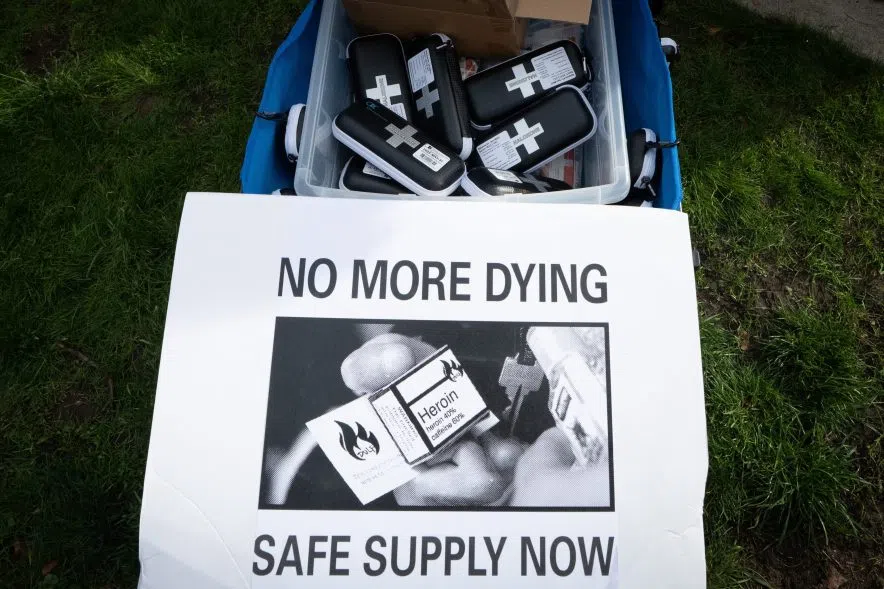

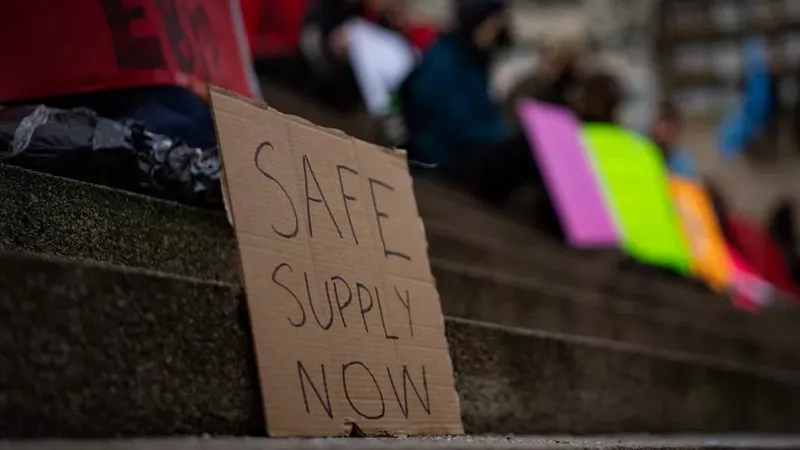

Saskatchewan’s government appears firm in its position to steer clear of implementing a safe drug supply or decriminalization as members watch B.C.’s drug policies unfold.

“I know the members opposite want to desperately convince the communities across Saskatchewan that there is somehow some safe use of an illicit drug. They want to flood our streets with needles and dirty crack pipes, Mr. Speaker, but that is not the strategy of this government,” said Saskatchewan Mental Health and Addictions Minister Tim McLeod in a recent Question Period.

Provincial ministers have also suggested that policies of other provinces, like safe supply and decriminalization in B.C., negatively impact Saskatchewan.

“That’s why we have to take the response we have to counter some of that because it’s truly toxic, and there are impacts across the country when one jurisdiction takes a certain approach,” said Justice Minister Bronwyn Eyre to the SUMA convention in response to a question about drug enforcement.