Justin Trudeau’s emergency law not the same as the one his father invoked in 1970s

MONTREAL — The similarities between Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s decision to invoke the Emergencies Act on Monday and his father’s use of a previous emergency law more than 50 years ago wasn’t lost on Quebec Premier François Legault.

“Of course I thought about that, what happened with the father in 1970,” Legault told reporters this week.

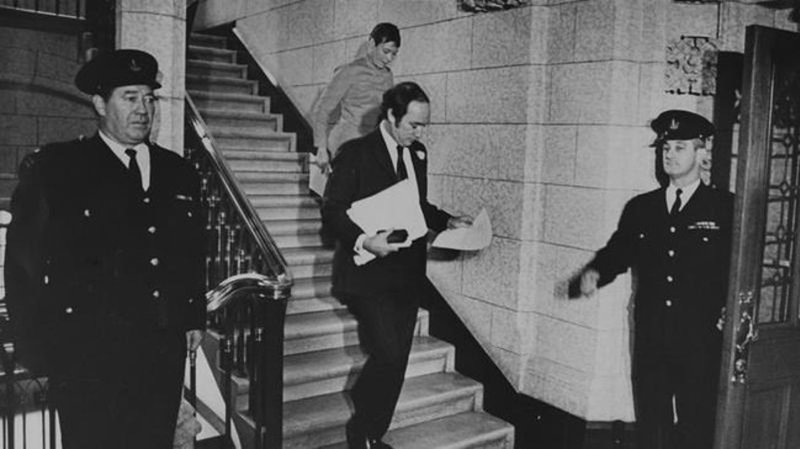

Then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act on Oct. 16, 1970, at the request of premier Robert Bourassa and Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau, after British diplomat James Cross and Quebec deputy premier Pierre Laporte were abducted by the Front de libération du Québec, a militant group that wasn’t shy about using violence to establish a Quebec state.

In 2020, Legault called on Justin Trudeau to apologize for the measures his father took by deploying the military in the province and arresting hundreds of Quebecers.