Desmond inquiry hears his firearms licence was reinstated despite police run-ins

GUYSBOROUGH, N.S. — Lionel Desmond’s licence to buy and possess guns was placed under review by firearms officials in New Brunswick in 2014 and again 2015, an inquiry into the former soldier’s death heard Wednesday.

But the mentally ill Afghanistan veteran — who shot and killed three members of his family and himself in Nova Scotia on Jan. 3, 2017 — managed to get his permit reinstated despite repeated run-ins with police.

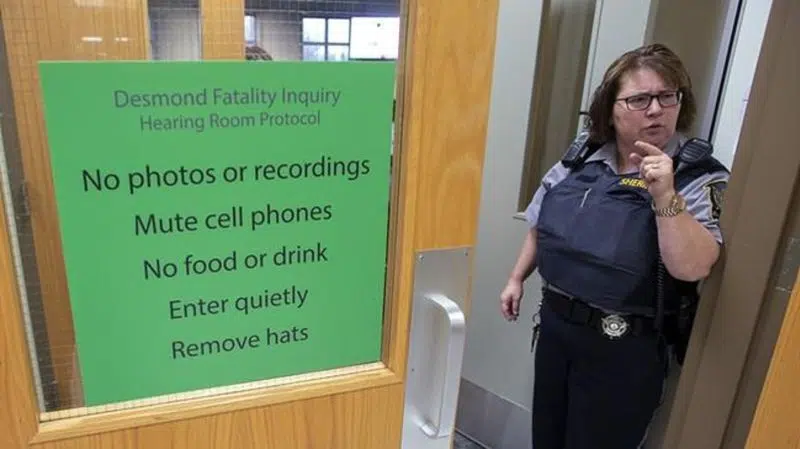

Desmond’s ability to legally buy a rifle on the day he killed his wife, mother, 10-year-old daughter and himself is at the centre of a provincial fatality inquiry that heard its 13th day of testimony on Wednesday.

The corporal with the 2nd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, was diagnosed in 2011 with major depression, severe post-traumatic stress disorder and a probable traumatic brain injury after serving in Afghanistan in 2007.