The case for Sister Carmelina’s sainthood moves from Toronto to the Vatican

GRAVENHURST, Ont. — Father Claudio Piccinini could use a few miracles.

For one, a miracle would really help Sister Carmelina Tarantino. She died in 1992, but a confirmed miracle now would send her sainthood application hurtling through to the next phase of the bureaucratic process in Rome.

The Archdiocese of Toronto recently wrapped up its 10-year investigation of Sister Carmelina and sent 10,000-pages of documents to the Vatican in November. She could be Toronto’s first-ever saint, but the process can take years — even centuries — to complete.

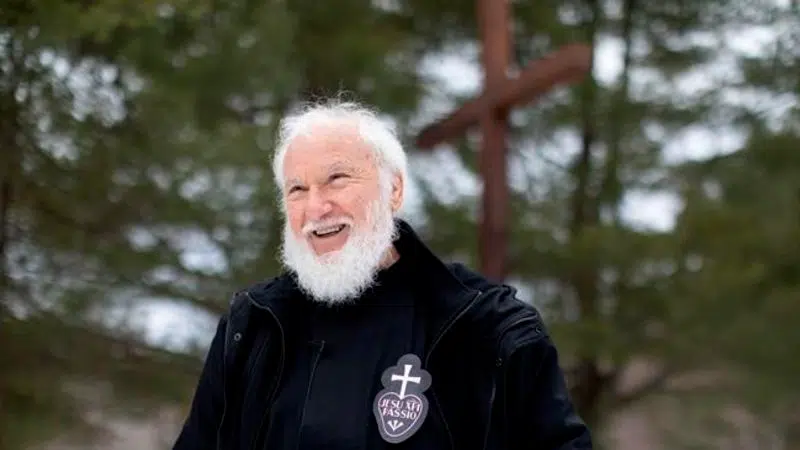

Piccinini, a 79-year-old Catholic priest who belongs to the Passionist congregation, does not have that long. His once-dark beard and curly hair have gone white.