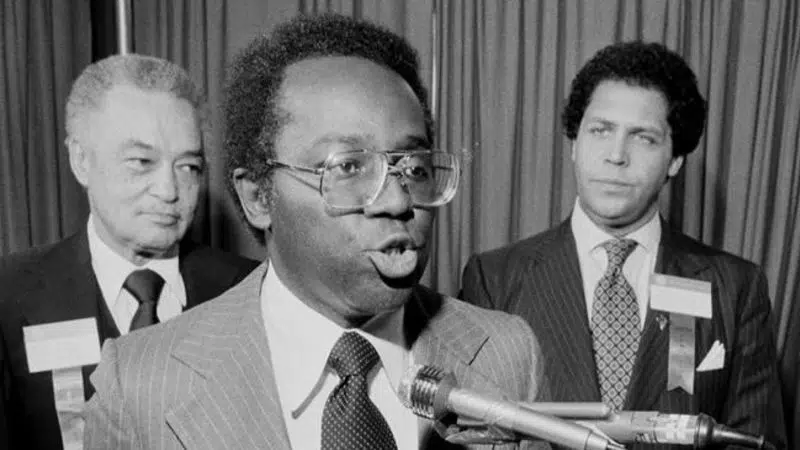

Former Gary, Indiana, Mayor Richard Hatcher dead at 86

Former Gary Mayor Richard Hatcher, who became one of the first black mayors of a big U.S. city when he was elected in 1967, has died. He was 86.

Hatcher died Friday night at a Chicago hospital, said his daughter, Indiana state Rep. Ragen Hatcher, a Gary Democrat. She did not provide a cause of her father’s death.

The Hatcher family said in a statement that “in the last days of his life, he was surrounded by his family and loved ones.”

“While deeply saddened by his passing, his family is very proud of the life he lived, including his many contributions to the cause of racial and economic justice and the more than 20 years of service he devoted to the city of Gary,” the family added.