How the First World War upended Canada’s political, social and economic norms

OTTAWA — The legacy of the First World War will be omnipresent when Canadians stop on Sunday — the 100th anniversary of the end of the War to End All Wars — to pay tribute to those who sacrificed for the country and its way of life.

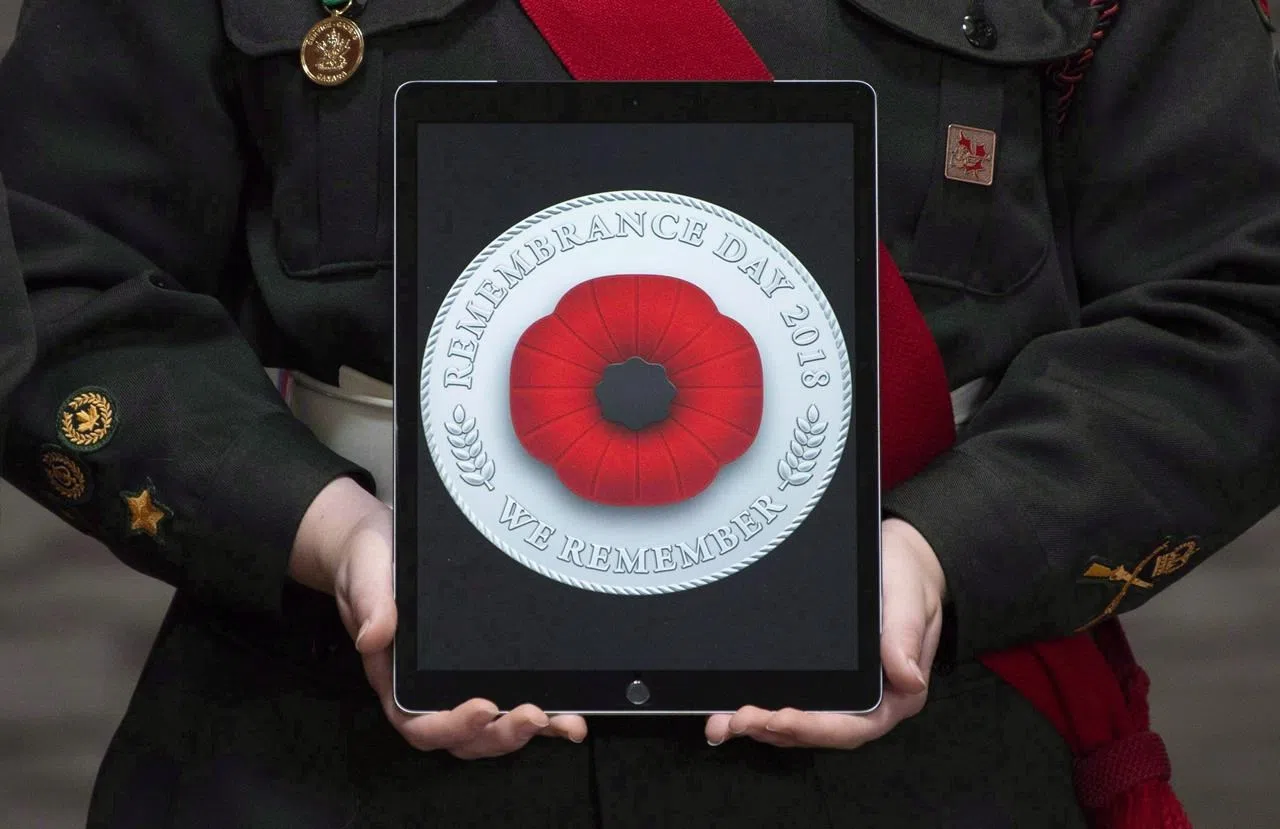

There will be the red poppies pinned to lapels, and the haunting words of In Flanders Field, penned by Lt.-Col. John McCrae after the Second Battle of Ypres.

There will be the National War Memorial, originally built to commemorate the 60,000 Canadians who died during the war, and Remembrance Day itself, which has been recognized every Nov. 11 — the day the Great War ended — since 1931.

Yet the enduring impact is felt in countless other ways as well, many of them subtle — and not all of them positive, despite the popular refrain that Canada came into its own as a country during the First World War.