Officer tells inquiry he thought he’d be shot: ‘This is going to hurt’

ST. JOHN’S, N.L. — The Newfoundland police officer who shot and killed Don Dunphy on Easter Sunday 2015 says he could only think “No!” as he suddenly saw a rifle in the man’s hands.

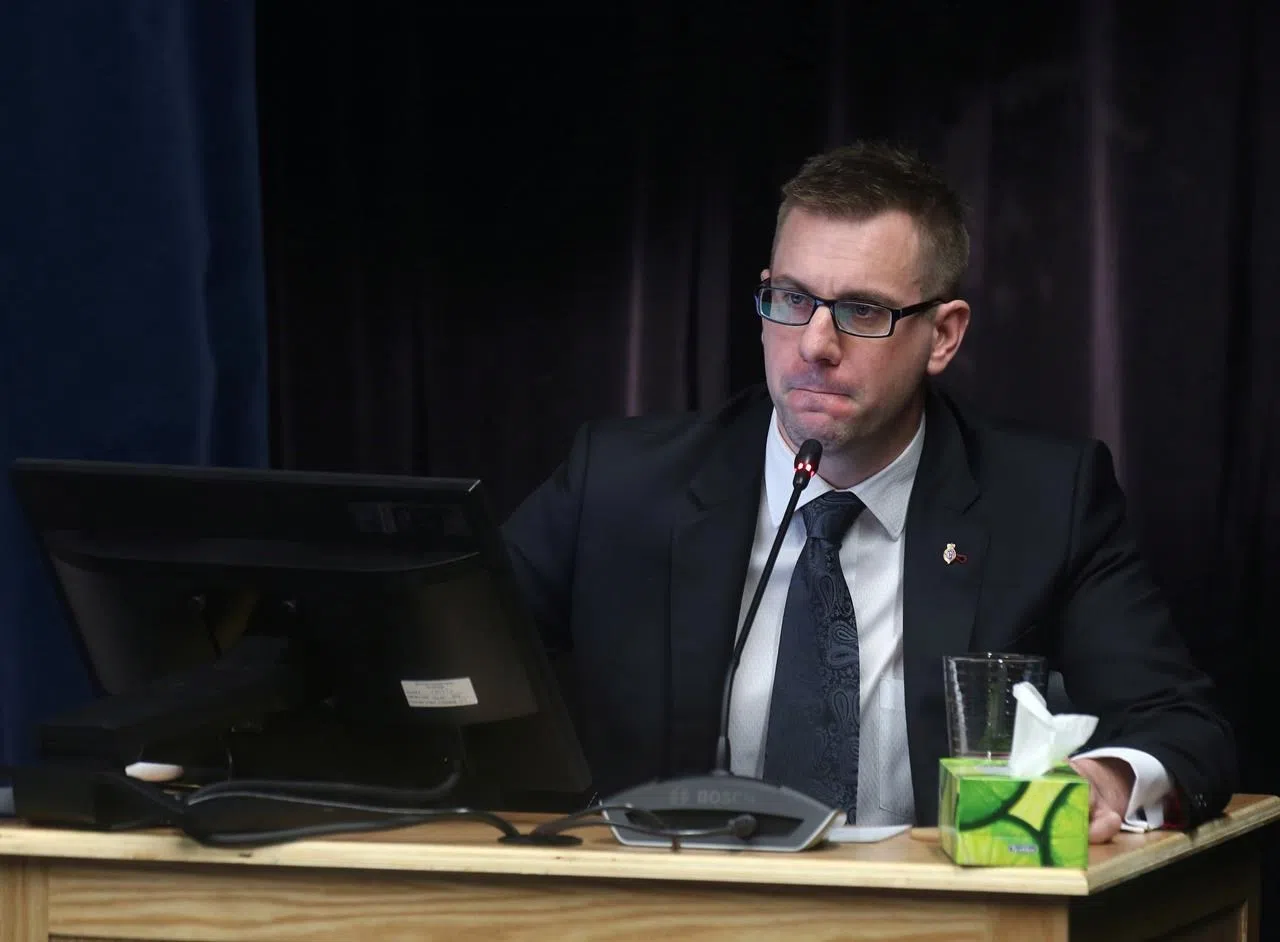

Royal Newfoundland Constabulary Const. Joe Smyth says he braced for impact, convinced he’d be shot.

He told an inquiry Wednesday into the killing that he took his eyes off Dunphy — contrary to his training — long enough for him to reach down to the right side of his recliner for the gun.

“By the time I focused on that firearm it was pointed at me. I thought I was going to be shot,” he testified.