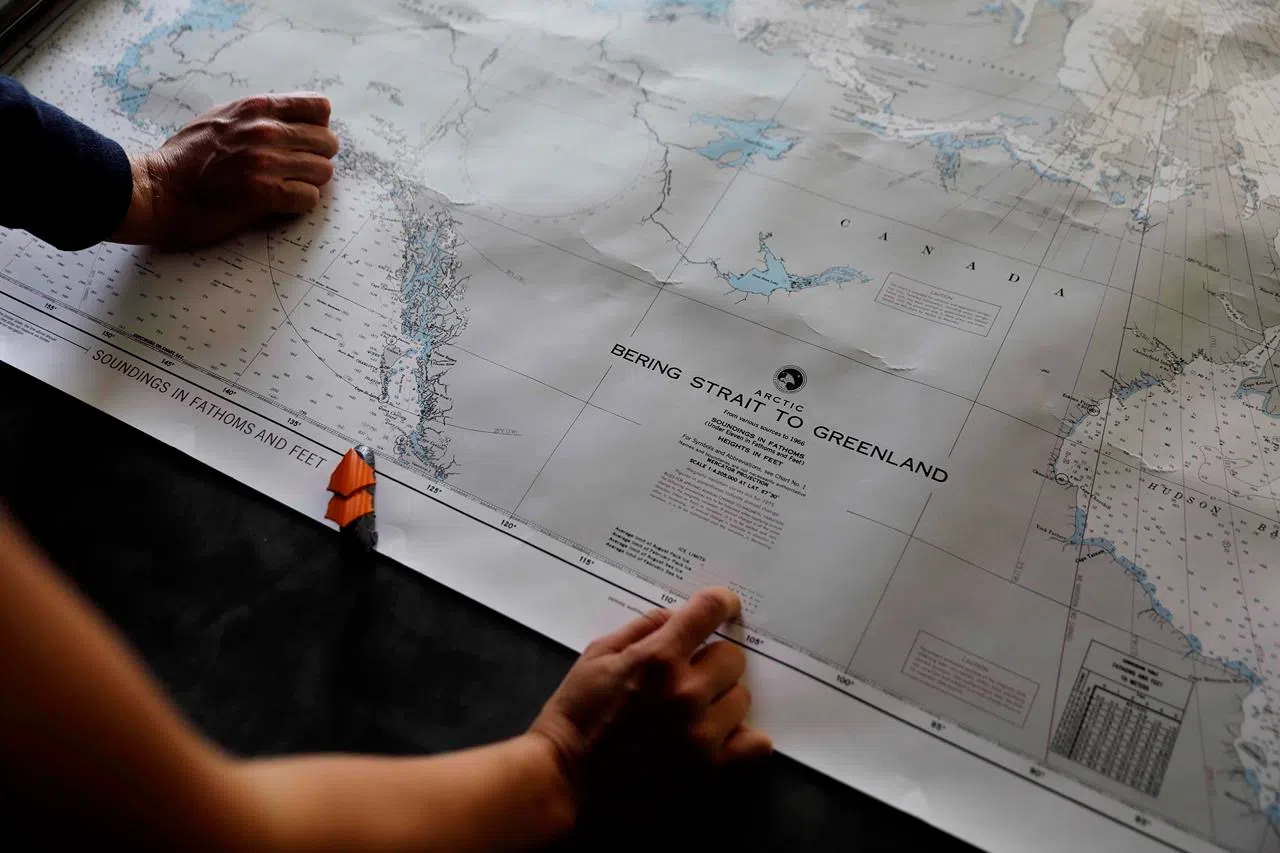

Canada not on board plan to ban “dirty fuel” use on Arctic shipping routes

OTTAWA — The Canadian government wants more study on the impact of eliminating heavy fuel oil in the Arctic before it signs onto an international agreement to ban its use there.

Sixteen months ago, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and then-U.S. President Barack Obama jointly committed to phase down the use of heavy fuel oils in the Arctic.

In an unexpected turn of events, the United States is keeping its end of the bargain under President Donald Trump. Last summer, the U.S. — along with Finland, Sweden, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Iceland and New Zealand — proposed that the International Marine Organization ban heavy fuel oils from Arctic shipping vessels by 2021.

Heavy fuel oil has been banned in the Antarctic since 2011.