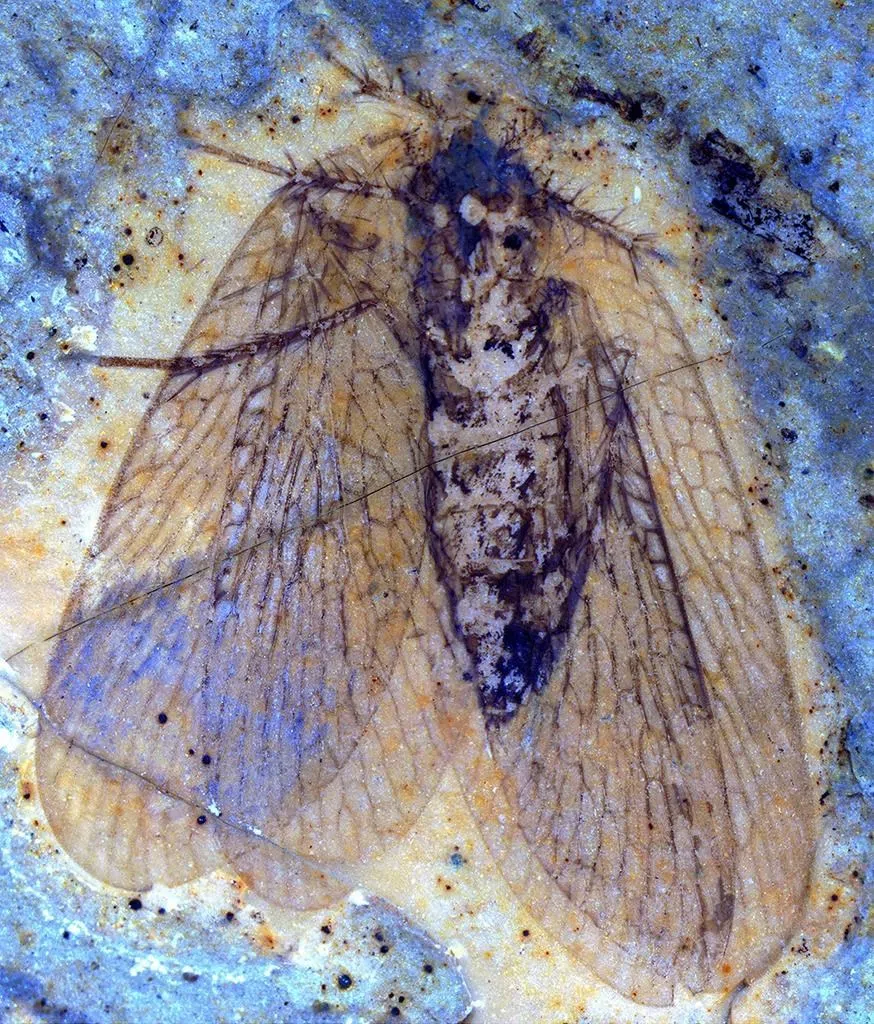

B.C. researcher’s identification of scorpionfly shows Canada-Russia connection

VANCOUVER — It seems Canada and Russia have a prehistoric connection of the “beautiful” but “cockroachy” kind involving a 53-million-year-old insect fossil called a scorpionfly.

Paleoentomologist Bruce Archibald of Simon Fraser University and the Royal BC Museum said the discovery in British Columbia’s McAbee fossil beds is strikingly similar to fossils of the same age from Pacific-coastal Russia.

A previous connection between the countries’ Pacific regions has been found in the same area near Cache Creek, B.C., through fossilized plants and animals.

Archibald said his identification of the colourfully winged species of scorpionfly found at the protected heritage site is another example of Canada and Russia’s ancient geographical link, before the continents split apart.